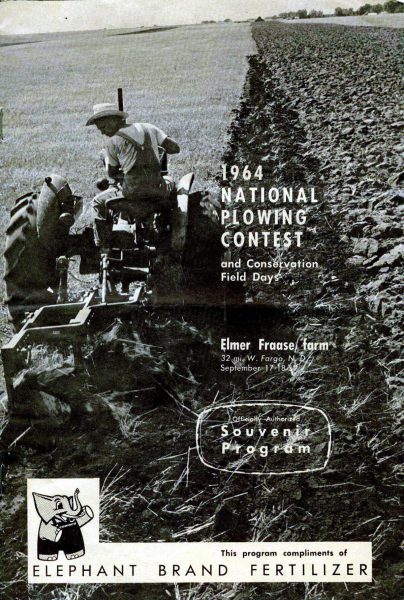

964 plowing contest drew 100,000 people to ND farm

Category: article

Aug 1st, 2019 by Keith Worrall

Modified Aug 1st, 2019 at 12:38 PM

964 plowing contest drew 100,000 people to ND farm

Ramona Fraase says her grandchildren aren’t sure what a plow is.

But plowing was important enough once to bring 100,000 people, including U.S. presidential and vice-presidential candidates, to her family farm near Buffalo, N.D., for the 1964 National Plowing Contest.

“It was a national thing. We did (news media) interviews from New York to Los Angeles,” Fraase says. “But it wasn’t about us or Cass County (in which Buffalo is located). It was about putting over North Dakota.”

Getting ready for the 1964 contest, held Sept. 17 to 19 that year, was a three-year process. Among the preparations:

• Turning cropland into hayland by planting 1,000 acres of alfalfa on the 1,500-acre farm.

• Assembling a 35-acre “tent city” for farm exhibits.

• Building a wide road from Interstate 94 to the farm.

• Planting 2,000 trees.

• Installing power lines and building a stage, airplane landing strip and communications tower.

Besides the actual plowing contest, the schedule of events included a banquet, concerts, skydiving, precision flying, fashion show, square dancing and election of a national soil conservation queen.

Fraase, 85, still remembers some of the queen contestants.

Politics also had a place at the three-day show.

Sen. Hubert Humphrey, D-Minn., his party’s vice presidential candidate, came and spoke. So did Sen. Barry Goldwater, R-Ariz., his party’s presidential candidate. Goldwater was trounced in the 1964 fall election by the Lyndon Johnson and Humphrey ticket and lost in North Dakota, too.

Fraase has photos of family members with both Humphrey and Goldwater. She remembers Republican and Democratic women preparing chicken together in her kitchen.

As Fraase notes, she and her husband, Elmer, who died eight years ago, had lots of help. Sponsors of the event included the North Dakota Association of Soil Conservation Districts, the North Dakota Broadcasting Co. and the Fargo Chamber of Commerce. Fargo, about 30 miles east of Buffalo, is the state’s largest city. Most of the event’s committees were led by Fargo businesspeople and soil conservation officials.

But Elmer and Ramona had a great deal to do themselves, especially since they had four children –10, 8, 5 and 2 years old at the time. “We were young, in our 30s, and had a lot of energy,” she says of her husband and herself.

Neighbors and others helped with the four kids, she says, stressing “our neighbors were wonderful.”

Ramona and Elmer, a third-generation farmer, grew up on farms 20 miles apart but attended different high schools.

Buffalo, which has about 200 residents, had about 240 in the early 1960s. The town is on the fringes of ancient Lake Agassiz, an area known for its flat, fertile farmland. That factored into the selection of the Fraase farm, Ramona says. They said yes. The idea of hosting an annual national plowing contest in North Dakota began in Ashley, N.D., in the late 1950s. Various organizations joined the effort later, in part to promote North Dakota’s 75th year of statehood in 1964.

A number of North Dakota farms were considered as potential sites for the contest. To be suitable, a farm had to be big enough, accessible to the public, provide a “showplace of North Dakota farming” and to incorporate the farming practices and geographic features needed to meet contest requirements, according to informational material for the contest.

The Fraase farm met the criteria, and in 1963 organizers asked Elmer and Ramona to serve as host couple.

“We thought about it. We were dumb enough to say yes,” she says.

‘Still kicking’

Today, plowing is uncommon in the Upper Midwest. New farming practices have caused most farmers to reduce their plowing or eliminate it completely. As Fraase says, many young people, even ones familiar with agriculture, know little or nothing about plowing.

Even so, there’s still an annual National Plowing Contest, now under the auspices of the U.S.A. Plowing Organization. The 2014 matches were held Aug. 15 to 17 in Beresford, S.D.

“We’re still alive. We’re still kicking,” says David Postlethwait of Springville, Iowa, president of the U.S.A. Plowing Organization.

He chuckles when asked about attendance at the 2014 contest. “We don’t get much attendance from the public. To the public, it’s like watching paint dry,” he says.

But the contest continues to attract competitors. U.S. winners go on to the annual world plowing contest, which also draws competitors from Europe, Australia, New Zealand and Africa.

The 2015 national contest will be held in Iowa, most likely in the first half of August. Details haven’t been worked out yet.

Iowa has always been a hot spot for plowing competitions. The first state plowing contest was held there in 1902, and about 250,000 people attended the combined national and world matches in Peebles, Iowa, in 1957.

The U.S.A. Plowing Organization is optimistic the 2019 world plowing competition will be held in the U.S. North Dakota is a possible location, with Fargo receiving strong consideration, Postlethwait says.

“We hope we can pull it all together,” he says.

For more information visit www.usapo.org.

Larry Hoffmann says he’ll attend the world plowing contest if it’s held in North Dakota. Hoffmann, of Wheatland, N.D., farms only a few miles from the site of the 1964 contest. He was a college sophomore that year and competed in the North Dakota state portion of the national contest.

“It was educational,” he says of the 1964 event.

Hoffmann still plows today, but only rarely.

“A lot of farmers, especially the younger ones, just don’t know about it,” he says.

A personal visit

Fraase will be available from 3 to 6 p.m. every Thursday in September at the Olde School, the renovated 1916 high school in Buffalo that’s owned by the Buffalo Historical Society. She’ll talk about the 1964 event, and a number of photographs from it will be displayed.

Serving as host couple was both challenging and satisfying, Fraase says.

She remembers seeing bare land when the 35 acres of tents were removed after the event ended.

“It had taken three years to get ready, and then it was all over,” she says. “It was work, yes. But we were glad to have been part of it.”