World-Famous or Legendary Muskie “Hotspots” – Part X

Category: article

May 3rd, 2021 by Keith Worrall

Modified May 3rd, 2021 at 11:23 AM

World-Famous or Legendary Muskie “Hotspots” – Part X

by Larry Ramsell, Muskellunge Historian

The St. Lawrence River

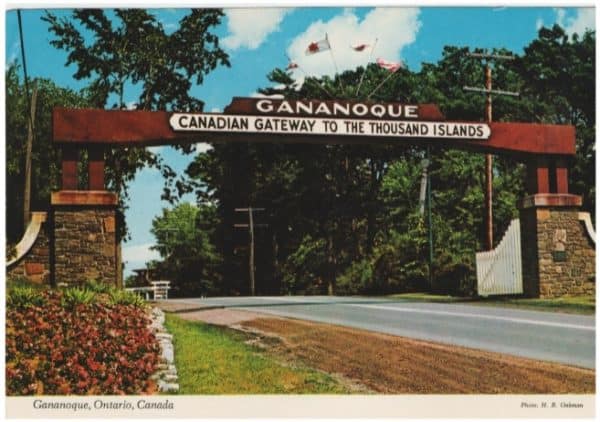

Canadian Gateway to Giant St. Lawrence River Muskies!

The St. Lawrence River (Fluve St. Laurent) is bordered by Ontario, New York, and Quebec. It is 743.8 miles long and just over 395 million acres with about one-half of that length (the western half) being great muskie water. As was the case with Lake of the Woods, except for the two “Hotspots” named by me in Part I , no one has come forward to share any other spots with us. So, as I did with Lake of the Woods, since The St. Lawrence River (Fluve St. Laurent) has been so important to muskie history and the “Chronological List of World Record Muskies” that I compiled for my “Compendium of Muskie Angling History” Volume I, 2007, I will list those fish. This BIG river (seven miles wide near the mouth) has contributed far more potential “world records” than any other body of water in North America! Here then, from my Compendium, are those records and potential records and information about same where known.

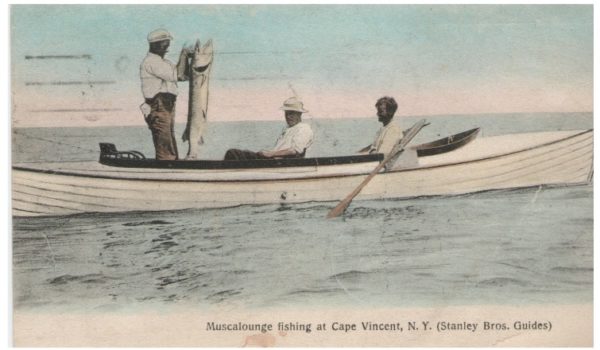

1907 Post Card of Cape Vincent, NY. U.S. Gateway #1

The “Cape” is at the mouth of the St. Lawrence at the Eastern end of Lake Ontario where the River is 7 miles wide!

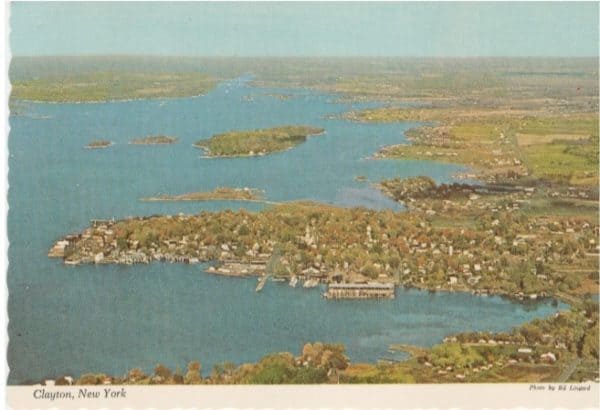

Clayton, NY, U.S. Gateway #2. Origin of the Skinner Spinner.

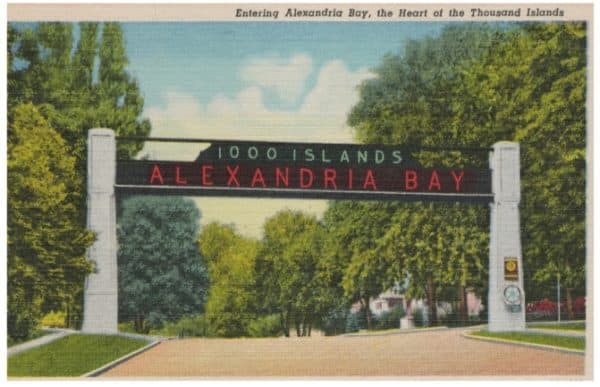

Alexandria Bay, NY, U.S. Gateway #3. Home of Heart Island and the Famous Boldt Castle & Yacht House nearby on the River.

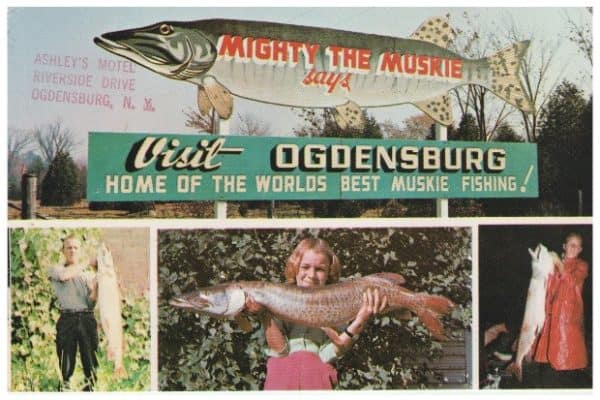

Ogdensburg, NY, U.S. Gateway #4

Area of the St. Lawrence River where the Hartman’s fished.

c/1877 Sydney Adams St. Lawrence River 50# 56”

No known photographic evidence or weight verification.

From the June 21, 1877 issue of Forest and Stream.

A fifty-pound muskelonge, a monster muskelonge (muskinonge), weighing 50 pounds, and measuring 4ft. 8 in., has been sent to John Cummings, of Utica, by Sydney Adams, Gananoque, Ontario. It is one of the largest ever caught in the St. Lawrence River. It was taken on a hook and line, and occupied the attention of the angler and Charley Lasha, his boatman, for over three hours.

This fish was never officially weighed or sanctioned and there is no catch story, but the possibility that it may have been legitimate gets it placed in the chronological list.

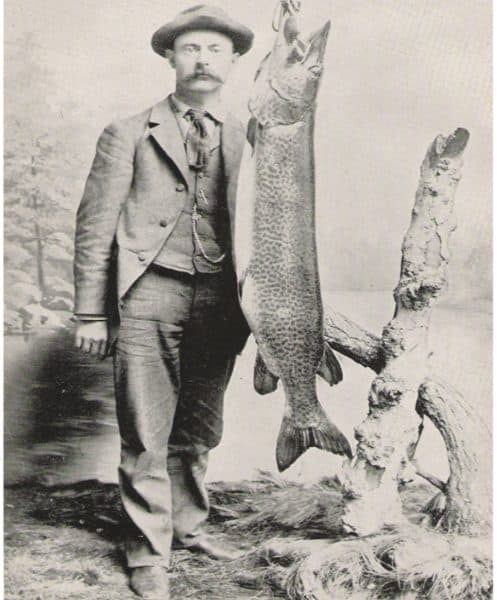

c/1880 Dexter Pillsbury St. Lawrence River 46#

Possible photographic evidence exists. No weight verification.

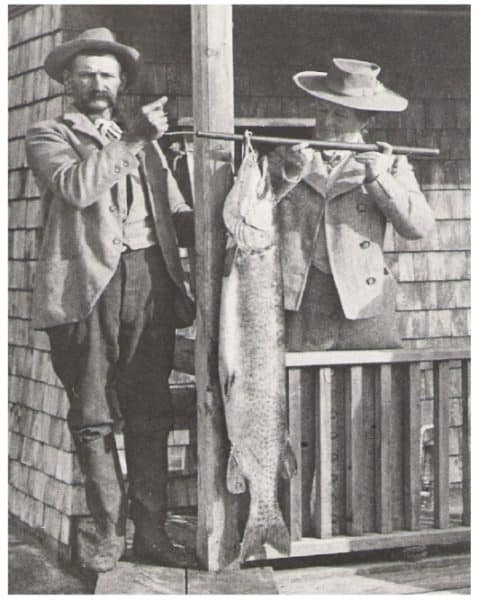

It was never officially weighed or sanctioned and there is no catch story, but the possibility that it may have been legitimate gets it placed in the chronological list. A possible photograph of this fish is extant and is shown above. In The American Angler in 1891 we once again see the lack of early record keeping, even within that publication. An article entitled The St. Lawrence Mascalonge Record, points this out vividly.

“Lascar is informed that the best record within our knowledge of Muscalonge caught in the St. Lawrence River is that of Mr. S. Dexter Pillsbury, who caught in one forenoon several years ago, three fish weighing respectively 46 lbs., 38 lbs., and 23 lbs. If this has been beaten, we do not know it. Do you?”

Yes, and they would have too, just by referring to their September 12 through October 31 issues of 1885 where the original information came from! Mr. Pillsbury’s largest fish noted above has been placed in the chronological list.

Could this 1880’s photo be of Mr. Pillsbury and his fish?

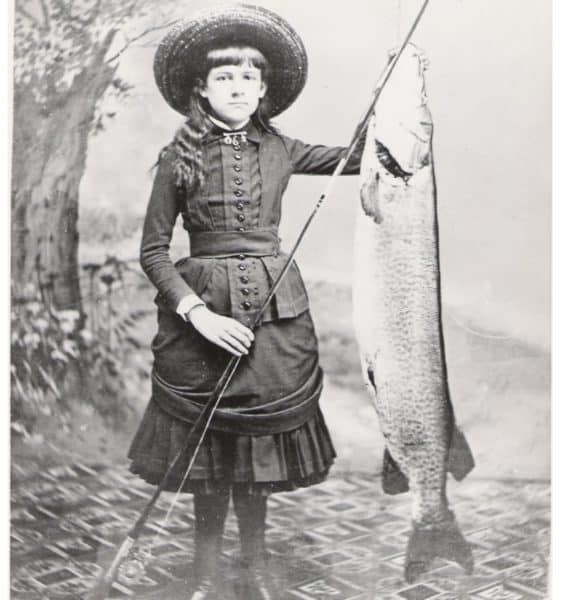

8/1883 Annie Lee St. Lawrence River 36#-2oz. 54”

May be the earliest angler & muskellunge photograph.

Weight is unverified.

In the chapter The Technique of Fishing from the book The Picturesque St. Lawrence River printed in 1895, I found a reference to a fish caught by a young girl which could be construed as the initial woman’s world record. To quote.

“A most unusual occurrence I would like to place on record. In August, 1883, Miss Annie Lee, at the time eleven years of age, while trolling near Clayton for bass, with a No.3 gold fluted spoon, which size is fitted with a No. 2 hook, struck and successfully brought to boat a muscalonge weighing thirty-six

pounds, measuring four feet six inches in length. In the effort to secure this large fish the guide’s gaff was broken, showing the enormous strength of the fish, yet it was finally secured, brought in, and exhibited with those slight hooks still fast in its capacious mouth, an evidence not only of good tackle, but of skillful handling.”

This fish was never officially weighed or sanctioned but the possibility that it may have been legitimate gets it placed in the chronological list.

Eleven-year-old Annie Lee

10/5/1884 J.T. Storey St. Lawrence River 46# 56½”

No known photographic evidence or weight verification.

The September 12,1885, issue of The American Angler carried a short story entitled A Monster Mascalonge:

“We had a pleasant call last Saturday from Mr. James T. Story, of Albany, who has added to our piscatorial picture gallery a photograph of the immense mascalonge (Esox nobilior) he had the good luck to capture in the St. Lawrence River, opposite Clayton, N.Y., on October 5th, 1884. We have no record of the catch of any larger St. Lawrence muskie. We should like to hear from any fisherman who claims to have captured a bigger one. Mr. Story’s prize measured 56 1 /2 in. in length and 24 in. in girth, and weighed 46 lbs. He had out 260 ft. of line, in 70 ft of water, when the fish struck and only a 2.0 triple hook below the spoon. The hooks were fastened in one corner of the fish’s mouth. The photo Mr. Story left with us is an excellent one, which we would be pleased to have our angling friends inspect.”

Story’s fish is added to the chronological list.

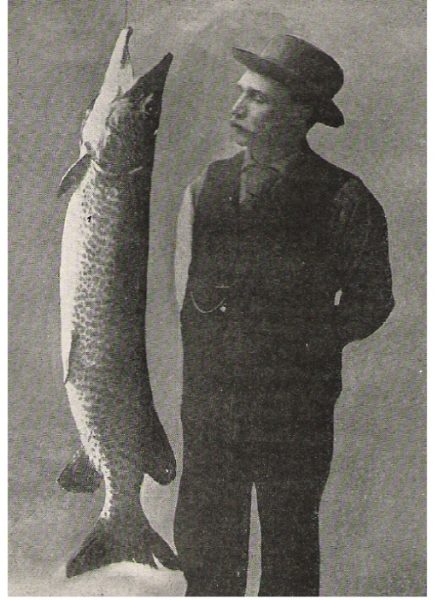

1893 G.M. Skinner St. Lawrence River 42# 55½” Photographic evidence exists. Weight is unverified.

G.M. Skinner St. Lawrence River.

This fish was never officially weighed or sanctioned and there is no catch story but the possibility that it may have been legitimate gets it placed in the chronological list. The fish was caught on Skinner’s own “spoon” which today is known generically as a straight-shaft spinner. Thousands of muskies were caught on Skinner Spoons in the late 1800’s thru the first half of the 1900’s!

This was found in an G.M. Skinner catalog, circa 1895:

“In 1873, G.M. Skinner started perfecting his fluted blade spoon in Clayton. N.Y., a bait that was to become the standard trolling bait in the late 1800’s. On October 6,1893 Mr. Skinner caught his World’s Fair Muscallonge. Caught on a No. 8 Gold Fluted Spoon, it weighed 42 pounds and was 55 1/2 inches long.”

The fish was caught on Skinner’s own “spoon” which today is known generically as a straight-shaft spinner.

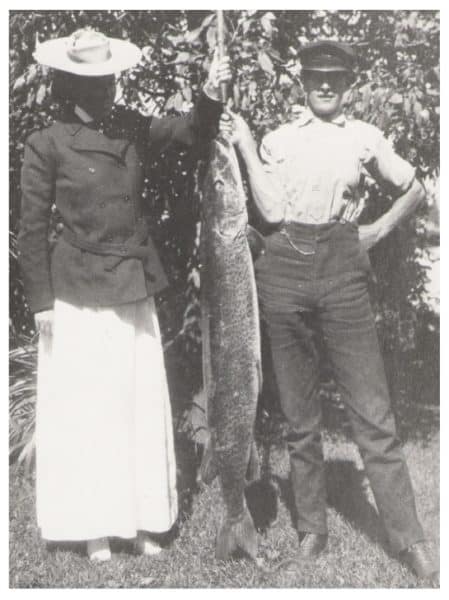

Mrs. Skinner

The above photograph is of Skinner’s wife with another large muskie and was provided to me by good friend Eddie Matuizek.

1904 Francis Bacon St. Lawrence River 40# 53”

Photographic evidence exists. Weight is unverified.

Mrs. Francis R. Bacon 40# St. Lawrence River

c/1905 -Mrs. William F. Morgan St. Lawrence River 43#

Photographic evidence exists. Weight is unverified.

The March/April, 1977, issue of The Conservationist magazine, a New York D.E.C. publication, brings us our second and third possible women’s world records. It is entitled The Magic of Musky Fishing by my late friend Harold E. Herrick Jr., who was a noted muskie historian on the St. Lawrence River at Cape Vincent, New York. A couple of excerpts follow:

“It was in August of 1904 that Grandmother Bacon tied into her large 40-pound musky near the large tree at Joyce’s Wolfe Island. I was told that this 53-inch fish surfaced many times with runs away from the boat. Some 40 minutes later, the still lively fish was brought along-side the skiff. Boatman Colon hand gaffed the gills and the fish was rolled into the boat and sat upon. The great moment of musky fishing ‘St. Lawrence River style’ had arrived with the ritual raising of a white flag, still practiced today.”

Mrs. Bacon and Mrs. Morgan flying the “muskie flag” after capture.

Last 3 Photo’s courtesy Harold Herrick Jr

This gives us our second and third possible women’s world records and two fish that have been added to the chronological list.

“During the many years, those two grand old fisherwomen, Bacon and Morgan, fished together, many large ‘lunge were boated with the largest Morgan catch being 43 pounds. The local newspapers reported the fishing exploits by these two summer resident ladies from New York City.”

Ah yes, it is great to see the ladies involved!

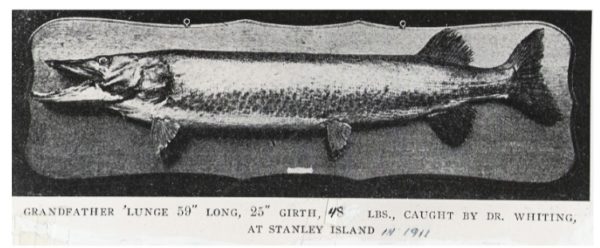

1911 – St. Lawrence River, Quebec Dr. F. Whiting 48# 59”

Naturally, since 1911 was the first year that records were kept and sanctioned, the largest muskie entered in the Field & Stream contest was destined to be a world record fish, regardless of its size. When the season ended and the contest ended, Dr. Frederick L. Whiting emerged from the files

Courtesy of Ken Schultz – Field & Stream

as the winner, and the then recognized world record holder with a 48-pound muskallonge from the St. Lawrence River on Quebec side of the border (second place that year was a 42-pounder from Chautauqua Lake, New York, by Allen A. Thayer). Dr. Whiting’s fish was not a case of blind luck as he had caught several large muskies in the past, and he again proved his capabilities in 1912 by taking 4th place in the same national contest with a 34-pound 8-ounce muskallonge from the St. Lawrence River, near Lancaster, Ontario.

Following is Dr. Whiting’s account of the capture of his record fish:

“It has latterly been the practice, therefore, of those of us who are out for the “big fellows” to tow our skiffs down the river by motor boats for a distance of about three miles and then to cast off and begin our day’s sport. Undoubtedly many fine fish dwell in the weed beds thus neglected and probably there are some old granddaddies among them which would well repay a fisherman for any labor expended in their capture, but the average size of the fish below Butternut Island will, I believe, exceed the dimensions of those taken above it.

“Within twenty minutes after leaving Stanley Island, Mr. Corbett and I were in our low-backed arm chairs from which the legs had been sawed off, permitting them to sit firmly upon the cross seats of the boat. Louis took the oars and began the gentle dipping stroke, which permits a trolling spoon at the end of eighty feet of line to play at about four feet below the surface of the water. I was using a split bamboo rod, while Mr. Corbett clung to his old and battle-scarred Bristol steel, to the whip like elasticity and lightning-quick recovery of which his unrivaled string of muscallonge killed within the last five years bears eloquent tribute. The lure we were both using was a Corbett spoon, the invention of my companion in the boat, and the most killing bait for big ‘lunge of which I have any knowledge. I have tried many varieties, patterns and sizes of spoons: I have trailed them with phantom minnows, and with gangs baited with chub, perch, and bass, with varying degrees of success, and after a fair and impartial trial I cannot too strongly endorse the Corbett spoon as the best tackle to be procured and the ideal lure for large ‘lunge.

“Having paid out our lines until the little red mark on mine indicated eighty feet, and that of my friend some fifteen feet less, we gazed at one another for a moment in an amiable but unspoken challenge, settled ourselves a little more deeply into the chairs, placed the right thumb firmly upon the reel spool, and were ready for business.

“As we paddled slowly along, with Louis casting his small black eyes furtively first upon one and then upon the other side of his boat, and peering down into the depths of the clear stream, in order that he might more surely hold his course at the correct distance from the edge of the weed beds, my companion, who possesses a positive genius for arousing these phlegmatic guides from their customary lethargy, said:

“Well, Louis, what about it? Do you think we will get ‘em to-day?”

“Louis crouched still lower over his oars, cocked his head slowly and cautiously to one side, and glancing up from beneath the brim of his weather-beaten hat, and assuming a look of the most guileful cunning, delivered himself of the longest speech on record. ”Yes siree! Dat’s de right – get ‘em sure! Dis day my eye he wink dat’s mean de good de luck! Can’t tell, might be get de big de ‘lunge!”

“Louis’ enthusiasm became contagious, and almost unconsciously we took a firmer grasp upon our rods, and tightened the pressure upon the reel spools, with a fisherman’s superstitious hope that so unusual and oracular an utterance might indeed have been inspired. Scoff not, ye doubting Thomases, lest your derision recoil upon your own heads, for never was a prophecy more speedily and literally fulfilled.

“We had crept along the upper edge of the weed beds below Butternut and were approaching a stake known as Martin’s buoy – so called because an Indian, Dave Martin by name, had stuck a pole in the mud at that point and decorated its top with an empty tomato can – when suddenly I had a strike, the force of which for a moment suggested that I had hooked fast to a trolley car going at a thirty-mile clip in the opposite direction. My answering strike was instantaneous and vicious, and was accompanied by as piercing a whir, as the line was stripped from the firmly held reel spool, as ever gladdened the heart and thrilled the pulse of a sportsman. I took a firmer grip upon the rod, raised its tip at a sharper angle, drew my feet firmly beneath me, and the fight was on. Three titanic, sagging heaves or rushes there were, following one another in lightning quick succession, each ripping off a few yards of my reluctant line and each compelling my good rod to bow its admiring acknowledgments until, bent in a quivering arch, its tip disappeared beneath the water. Three contemptuous messages of defiance from the fiercest and most courageous fish that swims the water were thus flashed up the line, before the gallant foe, his fury at being restrained fully aroused, consented to show himself. But having thus identified himself – for the short sagging rushes at the beginning of the fight, instantly announce to a ‘lunge fisherman the character and size of the game he has encountered – he disdained to fight longer under cover, and came to the surface with a mad, swirling rush that carried his great body entirely out of the water. Such a sight as this magnificent fish presented at the moment when, trying to throw the hook, he projected himself into the air, I cannot describe, but shall never forget.

“In the excitement of the moment, he looked as big as a motor boat, and as he remained poised for an instant in the air, his full length clear of the water, with his great jaws yawning wide, his blood red gills distended, and his fierce eyes rolling wildly, he certainly appeared the incarnation of Satan escaped from the infernal regions. Louis gazed spellbound in open-mouthed admiration, and then, as the leviathan plunged back into his native element with a tremendous splash, gave vent to the exclamation, “By gar, dat’s de big feller!” He then seized his oars and began turning his boat in a wide circle around the fish as a center. Mr. Corbett, while this preliminary skirmish was in process of completion, had rapidly reeled in his tackle in order that I might have a free field in which to operate during the ensuing encounter, and having placed his rod in the boat, he turned to me and remarked casually as he settled back to enjoy the scrap, “You seem to have connected with a small pike, Doctor!” I was too busily engaged with affairs of moment just then to frame an appropriate response to this bit of sarcasm on the part of my host, but I did manage to spare enough breath to reply, “If that’s a pike, he’s a corker,” and thereafter I had sufficient entertainment to occupy my attention with the business on hand.

When the ‘lunge first disappeared in that mad dive of his, he went straight to the bottom, and began to surge or heave on my line with such weight and force as to leave me no choice but to play it slowly out in order to relieve the great strain on the rod. This maneuver I was obliged to repeat frequently during the next few minutes, in order to save my tackle, and the snitch of the reel click, as yard after yard was reluctantly yielded, became an anxious and worrisome sound, for, as all fishermen know, every yard of line that a game fish, especially a big one, gets beyond forty, increases the hazard and danger of losing him by a distressing percentage, and increases the likelihood of his pulling off some successful stunt to the angler’s undoing.

“Louis was working valiantly at the oars in an ever-widening circle, and exhorting me to hold him, for to Louis every snitch of the reel as the drag of the ‘lunge pulled the line from beneath my thumb, was like a stab in the vitals. He thought I was tempting fate and ejaculated between strokes – “You lose – you lose sure!” – but I knew how much the rod would stand, and I did not dare hold any harder. I also knew that no fish could endure such a strain for any length of time, and expected every moment to see the rod straighten as the ‘lunge began to tire. But he was an 18 karat fighter and a foxy fellow to boot, and his next little piece of strategy nearly caused me heart failure, for I thought I had seen the last of him.

“Just before he broke for the second time, I was still holding firmly against his brutal and obstinate drag, when suddenly the rod tip leaped upward, the strain upon my wrist was relaxed like an automatic cut-off from an electric switch, and my line hung slack and dangling in the water. The consternation depicted upon Louis’ countenance at this junction would have been a most comical sight to a disinterested spectator – but there was no such person in the gallery – his oar blades hung motionless in the water, his jaw dropped, and a sigh as long as your arm escaped him, together with a despairing cry of “By Gar, he gone!”

“My fellow fisherman said nothing, for the same idea had occurred to each of us simultaneously, and I reeled in with all possible speed, in the hope that the ‘lunge had suddenly taken it into his head to stop fighting the rod, and to rush the boat instead. As good fortune would have it, my idea was correct, and immediately I had recovered the slack line and raised my rod tip with a snap, I received a jerking tug that was joyfully reassuring. “Pull, Louis,” I yelled, “he’s on!” The oars lashed furiously into the water in a frantic effort to regain our lost headway, and so fierce was the stress of Louis’ excitement and so sudden his physical exertion, that at that precise moment he swallowed a large and juicy quid of tobacco which he had previously been holding between his clenched teeth.

“The fight was now at shorter range, and I became conscious of a growing feeling of mastery of the situation. My wily foe had played two of his high trumps, but the control was still in my hand, so I proceeded to put on the screws. As I increased the strain upon the rod, he refused to yield an inch, and there was telegraphed up the tense line to my tiring wrist a feeling of grinding and grating caused by the crunching force of his iron jaws and hound-like teeth upon the spoon and gang of hooks which he was trying to crush. The sensation thus conveyed to the fisherman is like nothing in the world so much as the feeling of broken bones grating upon one another, and is characterized by the doctors as “bony crep-itus.” Of all the sensations which a captive fish at the end of the line affords to the angler, there is none, I believe, that imparts such a sense of keen gratification and delight as this rasping, grating vibration, for it signifies that you have met a foeman worthy of your steel, an antagonist who still has enough fight in him to grind his teeth with fierce determination, and to whom the prick of the hook, so far from being an inducement to quit, is rather a spur to more furious resistance.

“But while the courage of the muscallounge is boundless, and although he possesses an unconquerable spirit, there is still a limit beyond which the power of flesh and blood may not endure. The lessening strain on rod and line told only too plainly that the terrific struggle which the fish had so gallantly sustained was telling on him and was rapidly reducing his strength. Therefore, I determined not to allow him any time for a breathing spell, appreciating full well that such a rest would surely contribute to his capacity for making mischief. Up to the present moment the angler had been entirely on the defensive, but now he determined that the psychological moment had arrived to push home the attack.

“I raised my tip sharply, and obedient to the steady upward pull of the rod, the fish again shot to the surface, coming up straight out of the water for about half his length he supported himself momentarily in this position, and shook his head until the spoon protruding from his yawning jaws rattled like a dinner bell, thus serving notice upon us that, although growing tired, he was by no means “all in.” A sharp pull at the oars by the vigilant Louis, and a quick backward snap of the rod, prevented the fish from gaining any slack line during this maneuver, and as he plunged again into the depths, I realized with a grim sense of satisfaction that his speed was much reduced, that he seemed to swim down with an effort, and took but little line from us, whereas, on his first plunge, he had gone down with the speed of an express train and to the high pitched accompaniment of a singing reel.

“Four successive times, under the steady strain of the relentless rod, he came to the surface, still battling as fiercely as his rapidly waning strength permitted, until at length, completely exhausted and unable to overcome the spring of the rod, he turned upon his side, his great gill covers spread wide, his chest heaving deeply, and his fierce eyes proclaiming his unspeakable and impotent rage.

“As he lay thus, feebly waving his fins, but a few feet from the boat, he was a picture to arouse the unqualified admiration of a sportsman. Never have I seen so grand a fish, and I gazed at him almost loath to administer the coup de grace. Not so Louis, who was fairly exhaling the spirit of primeval savagery, to whom stern experience had taught the truth of the oft-told adage, “there’s many a slip twixt the cup and the lip.”

“’Shoot him! shoot him!’ he shouted, reaching forward for his gaff. Mr. Corbett pushed up the safety clip of our little .22 rifle, and said quietly: ‘Bring him around a little to the side, Doctor, and I’ll shoot him.’

“But the momentary rest which our prospective victim had enjoyed while enduring our admiring scrutiny, had somewhat restored his strength and afforded him an opportunity for one last display of his indomitable courage. With a swish of his tail and a boring, wriggling motion, he lunged downward under the stern of the boat, in a last despairing effort to foul or break the tackle. But, though the spirit was willing, the flesh was weak, and exhausted nature was unequal to the task. A good sharp pull on the right oar, and a quick jerk of the rod to the left, brought him promptly to the surface again, where a shot through the spine mercifully dispatched him.

“As we brought him unresisting alongside the boat, preparatory to taking him aboard, Louis, still greatly excited, called out, ‘Take de gaff! Take de gaff I ‘fraid you lose!’ – at the same time pushing that instrument toward my companion. But the boss ‘lunge fisherman disdaining this cautious injunction, reached out his hand and quickly eye-holed him into the boat, notwithstanding his great size and weight. Louis, now wreathed in smiles, promptly clutched the fallen monarch and thrusting him forcibly under a seat amidships, covered him with a rug upon the sides of which he firmly planted his feet, for such an unbounded respect has he for the ability of a muscallonge to get away, that he never feels quite at ease regarding his quarry until he sees him hanging safely on a hook in the icebox at Stanley Island.

“It was a gallant struggle, and an experience in which one lives a year’s duration in the short space of half an hour. It was also a fair fight, in which the angler matched his skill against the fish’s strength and courage, and the exultant thrill which the fisherman experiences in such a victory, serves to mitigate the mortification and diminish the sting of many a previous defeat.

“As Butternut Island was near at hand, we decided to go ashore in order to cool off a bit and to scrutinize our capture more carefully and leisurely. When stretched upon the grass, he measured fifty-nine inches in length, and about twenty-five inches in girth. His weight upon a standard scale when we returned to Stanley Island was an even forty-eight pounds.

“This fish had been hooked at the base of the tongue, and was therefore at a great disadvantage in fighting for his life. Had he been hooked in his hard and bony jaw, I believe he would have tested my tackle and skill far more severely, and might even have had the better of the argument.

“As I gazed upon the beautiful fish and thought of the magnificent sport his splendid courage had afforded me in our recent encounter, I could but wonder that any person in whose veins circulates good red blood, instead of ice-water, could fail of an enthusiastic appreciation for the matchless fighting spirit of the ‘lunge.

“As for me, I have long been thoroughly inoculated with the bacillus of muscallongitis, a germ not commonly mentioned in standard works on bacteriology, and lest some inquisitive reader should desire to learn the definition of the term, and should not have access to the latest edition of the medical dictionary, I hereby gladly furnish the desired information:

“’Muscallongitis’ is a progressive malady, characterized by certain bilious and unappreciative observers as a harmless form of mania, for the taxaemia of which there is no known antidote. It terminates only with life, and but one single remedy has ever been found effectual in temporarily arresting its most violent manifestation, and that is for the victim of the disease to take as often as opportunity permits a hair of the dog that bit him.”

“Muscallonge caught on September 3. 1911, on St. Lawrence River (Quebec), below Stanley Island, near Butternut Island.

“Weight, 48 pounds; length, 59 inches: girth, about 25 inches.

“Tackle used: Split bamboo rod, made by Von Lengerke and Detmold: weight, 12 ounces: length. 7 feet 6 inches.

“Line, 300 feet of braided linen. No. 4, Vom Hofe reel.

Large brass swivel and three-foot copper leader. No. 9 Corbett spoon, with feathered gang of three large hooks.”

c/1919 Alphonse Allard St. Lawrence Riv., QC 60#

Not entered in the Field & Stream contest. Reported weight exceeded the Field & Stream record. No known photographic evidence or weight verification. Not recognized by Quebec.

Alphonse Allard’s 60-pound muskie caught from the St. Lawrence River, Quebec, was never officially weighed or sanctioned and there was no catch story but the possibility that it may have been legitimate gets it placed in the chronological list since it was reportedly larger than the world record at the time of the catch.

In the 1922 publication of the American Fisheries Society a chapter was written by E.T.D. Chambers entitled The Maskinonge: A Question of Priority In Nomenclature. From that chapter comes the following.

“A few years ago, the Ontario Department of Fisheries at Toronto received a magnificent specimen of maskinonge, over five feet long and weighing fifty-two pounds. It was caught in the branch of the Rideau River, which passes through Kemptville, by Sam J. Martin, of Kemptville. Big as this specimen was, it has been cast altogether in the shade by a capture by a French Canadian, Mr. Alphonse Allard, at Chateauguay, on the border of the St Lawrence, a little west of Montreal. This monster, which was sixty pounds in weight, had a girth of twenty-seven inches. The length of the head from the tip of the snout to the back of the gill was exactly a foot.”

9/22/57 Art Lawton St. Lawrence Riv., NY 69-15 64½”x31¾”

1957 Field & Stream contest winner and world record.

The fish was sanctioned by Field & Stream following a lengthy investigation which reportedly included use of the Pinkerton Detective Agency. Photographs, weight verification and witness affidavits exist. Additional affidavits were obtained in 1992. The fish was not mounted. A professional photogrammetric analysis has not been commissioned. The fish is recognized as the New York state record muskellunge, however; the record was disqualified by the NFWFHF and set-aside by the IGFA in 1992 following a challenge by John Dettloff. Dettloff’s investigation was rejected by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation and deemed inadequate by the IGFA. The record remains in set-aside status by the IGFA because their retroactive requirement for an appropriate photograph was not met in either 1992 or 2007, according to them.

The King!

1957 – Arthur Lawton St. Lawrence River 69# 15oz.

Almost eight years had passed by and Louie Spray was still the world record holder for muskellunge. Other than Malo’s challenge, nothing came close until 1956, when the husband-and-wife team of Art and Ruth Lawton combined to take first and second place in the annual Field & Stream and New York State contests after Art had also taken first place in 1955. An interesting note here is that the first-place 1956 fish caught by Ruth was also the first 60-pound muskie entered since the Spray fish, and the first 60-pounder ever claimed by a woman. As time would tell, this 1-2 finish in 1956 was no accident. It would happen again in subsequent years not to mention their many other contest finishes in the top four. This couple had learned the secrets of the St. Lawrence River waters in New York, Ontario and Quebec and were about to write a chapter of their own in the history of muskie fishing. In 1957, Art submitted to Field & Stream a contest entry for a 69-pound 15-ounce muskellunge. Art’s story as written by others follows.

“Art Lawton started muskie fishing in 1936 when his brother Gordon introduced him to the sport. They fished Lake St. Francis, before a widening of the St. Lawrence River, created a different “lake” with the building of the St. Lawrence Seaway with it many dams. It was here that Gordon had begun his muskie fishing only two years before. On that Labor Day weekend, Art caught a 25-pounder and that did it, Art Lawton had caught “muskie fever.” He never looked back.

“A year later, he was joined by Ruth, and as it turned out, she liked muskie fishing as much as he did, and the two of them fished together thereafter until Ruth died, when Art all but quit muskie fishing. Art and Ruth started catching quite a few muskies in the Clayton, NY section of the St. Lawrence River about 1940 and continued fishing that area for over a quarter of a century.

“In 1944, Art caught his first really big muskie, a 58-pound 5-ounce giant on November 5th using a Heddon Vamp Spook. It turned out that his fish took first place in the Field & Stream contest that year and from then on Lawton sought only trophy sized fish, fish he thought would win the Field & Stream contest.

“Art didn’t place again in the Field & Stream contest until 1955, but brother Gordon took second place in 1951 with a 50-pound 7-ounce fish from the St. Lawrence. Art’s 1955 fish placed first in the Field & Stream contest and weighed 58-pounds 13-ounces, again caught on a Heddon Vamp Spook on October 2nd. This fish also took top honors in the New York State contest sponsored by Louis A. Wehle, a former Conservation Commissioner of New York. But then in 1956, Art only finished second in both contests with a 52-pound 5-ounce fish caught October 4th. He was outdone by his wife Ruth, who caught a 60-pound 8-ounce beauty on September 16th, using a Pflueger Buffalo Spoon.

“Ruth’s fish was the first 60-pound muskie that the couple had ever caught, and it was also a new State record for New York. 1956 was the best year of muskie fishing that they had ever encountered up to that point. In a one week stretch, they had landed 19 muskies over 20-pounds, including Ruth’s 60 ½-pounder.

“This was a result of Art’s new theories and methods of muskie fishing which were mostly experimental, applying methods he had learned to catch northerns and walleyes, to muskies. Here they went through a cycle of natural baits, bucktail spinners and spoons, and finally arrived at plug fishing. It was about 1950 when Art decided that plugs were the best suited for their style of fishing. Shortly after they started using the Creek Chub Pikie Minnow is when the big muskies started to fall. Ruth preferred the 6-inch model as it had less drag on her line, and Art liked the 8-inch model as he was only after large muskies and fish under 20-pounds didn’t interest him. Their switch to the Pikie was because Art like the motion it had in the water and the construction was better than that of most baits they had used in the past. He tested each Pikie he used by watching its action behind the boat while trolling. He eliminated those with no motion and those with a frantic, too-fast motion. He looked for those that had a moderate-steady “S” motion as it was trolled at 4 miles per hour. They used either the solid body or the jointed Pikie’s and interchangeably as they felt both worked equally well provided they had the “S” motion. The colors they used were those with a high visibility and yet natural like the baitfish of the watershed they fished.

“For the Lawton’s, fishing in 1957 was much the same as any other year until one week in early September when they boated 30 muskies and lost 5 others. Of those 30 fish, they kept only nine to take home. The other 21 were released unharmed by working them free of the hooks without boating them. That was their standard practice as they didn’t eat muskies (they preferred walleyes for eating) and only kept the very big ones, or those hooked too bad to release.

“The 9 fish weighed between 20 and 49 ½-pounds. They were troubled by the fact that thus far they had not caught a muskie in the record class and felt they lacked a solid entry that would place high in the Field & Stream contest. So, one week later, they made a return trip to the St. Lawrence River hoping to catch a prize winner.

“Fishing on that Saturday was nothing spectacular as they landed only a 20 and a 28-pounder. Then on a cool, hazy-overcast Sunday at approximately 4 p.m. September 22, 1957, while trolling a grassy shoal between Clayton, NY and Gananoque, Ontario on the New York side (reported in some accounts as closer to Gananoque on the Ontario side, but submitted to Field & Stream as having been “St. Lawrence River, NY”-LR), Art hooked into something he thought at first was the bottom. He had been trolling with 100 to 125 feet of line; thus, his bait was running down close to the bottom in water 25 feet deep. The line held tight and Lawton then cut the motor, but still nothing moved. Then as suddenly as the bait had stopped, the line started throbbing and Art knew instantly he was into a good fish. The muskie held its ground for about a half hour, staying deep and “slugging” it out with Lawton the whole time, doing whatever she pleased. The fish then made a quick move off the bottom, rising to the surface. It was then that Lawton got his first good look at the fish and confirmed his thoughts of a “huge” muskie. The fish broke water, smashing the surface, swimming back and forth, making short runs towards the bottom, but yielding to the rod pressure that Lawton exerted to keep the muskie up.

“Finally, after about an hour, the big fish began to “wallow” on the surface and regurgitated a two-pound northern. When the big muskie came belly up at boatside, Lawton knew that she was done and Ruth then gaffed the fish, and then only by a strand of ligament along the outer edge of the upper jaw. He immediately dropped his True Temper rod, equipped with a Shakespeare reel with Ashway nylon line and helped lift the muskie over the side of the boat.

“When it was all over, they knew it was the biggest muskie they had ever taken, but the thought of a world record never occurred to either of them.

“They had always waited until they got home to weigh their catches, and they treated this fish like all the other big fish that they had taken in the past. They quit fishing, went ashore, packed the big muskie on ice in the trunk of their car, and drove the 200 miles back to Albany where they put the fish in a cooler at a storage warehouse where Art worked as a refrigeration engineer.

“The following evening Art took the fish to Walter Dunn’s slaughterhouse in Albany where the muskie was laid on the scale and weighed at 69-pounds 15-ounces, almost 30 hours after being caught and having regurgitated up a two-pound pike while being fought.

“It measured 64 ½-inches in length and was 31 ¾-inches in girth. People gathered to check the weight and no mention was made of it being a possible world record, and Lawton was only thinking of the Field & Stream contest.

“He then froze the fish until the following Sunday at which time he hung the fish in his front yard for the neighbors to see. That night he gave the fish to his brother Ernest who liked to eat muskies and at the same time divided the other 9 muskies from the earlier catch among his friends.

“Why didn’t Lawton mount the fish? He and Ruth didn’t fish for mounted trophies as they were unable to afford the cost at the time, and they were just out there to have fun and enjoy the thrill of doing battle with the biggest freshwater game fish in North America. Lawton didn’t treasure mounted muskies as most of us do now; in fact, four of their muskies which were mounted eventually found a place in his attic gathering dust (witnessed by this “Compender” when I visited Lawton at his home in 1977). Lawton never fished for records or to impress others, he just fished for muskies because he liked to catch them.

In his July 20, 1978 article; Anglers at Leech will find muskie record a mouthful in the Minneapolis Tribune Ron Shara wrote the following, in part, about Art after I had invited him to come to Minnesota and fish the Muskies, Inc. International tournament with Lou Cook and I.

…”Fishermen are eternal optimists. Why couldn’t a world record be swimming in Leech Lake? Who could dispute such a contention?

“After all, Art Lawton was looking for a 100-pound muskie when he tangled with one that weighed 69 pounds 15 ounces.

“I really wasn’t excited at the time,” Lawton explained the other day over the telephone. “It was just another fish.”

“But that 69-pound, 15-ounce muskie turned out to be the official world record…

“’I just took my time,’ Lawton, now 69, recalled. ‘I knew it was a good fish but I wasn’t in any hurry’…

“’We never talked to anybody on the river,’ said Lawton. ‘Ruth and I always figured that fishermen should have to learn to catch muskies the way we had to…’

“The Lawtons returned home. That night Lawton, a refrigeration specialist, took the fish to work and put it in a cooler. There would be time later to see how much it weighed.

“The next day Lawton hauled the fish down to a local locker plant.

“Lawton was impressed when the scale read 69 pounds, 15 ounces, but not irrational. He couldn’t afford to have the fish mounted so he gave it to a neighbor. But he sent a note off to the Ashway line company about the catch.

“’A week or so later I got a letter from the company, telling me that my muskie was the world record,’ said Lawton. ‘That’s the first time I knew about it.’

“He doesn’t do much fishing anymore, particularly since Ruth, his wife and fishing companion, died several years ago. However, Lawton has been invited to fish Leech Lake, Minnesota, during the Muskie’s, Inc. International Muskie Tournament in September.

“’I’m still planning to be there,’ he said. “There’s more interest today in the world record than when I caught it. No, catching the world record didn’t make me rich. I think it could have, but I was too dumb, I guess.’

“So were Lawton’s neighbors. They ate the world record.”

And yes, Lawton did make the over 1100 mile drive out from his home in Delmar, New York to Minnesota by himself even with the heart condition that he had. During his visit he related to me that one week after he caught his record catch, he lost an even larger one!

We went to Lake of the Woods after the tournament for five days to fish with Dr. Jerry Jurgens and Bob Kimitch. Lawton then made the long drive home. Two months later Art died.

Besides Art’s world record, the Lawton’s claimed several 60-pounders including Ruth’s 68-pound 5-ounce monster caught in 1961 and a 60-pound 8-ounce muskie taken in 1956, while Art claimed a 65-pound 13-ounce muskie in 1959 and 61-pound 4-ounce muskies in 1960 and 1962! They dominated the Field & Stream contest until 1962.

After that time, their names were no longer seen as the Field & Stream contest format was changed and they kept pretty much to themselves and enjoyed muskie fishing alone without the ever-present shadow of other eager muskie fishermen. The completion of the Seaway also gave the river a new personality and muskies no longer were found where they had been in the past. Nevertheless, the Lawton’s were well known throughout muskie country and to this day hold first and third on the all- time verified list of muskellunge catches.

Lawton with a 65# 13-ounce Giant caught 2 years after his record catch. Even Dettloff didn’t question the size of this one!

The Queen-Ruth’s massive 68-5 that was 61 ½-inches long.

Since this last Part is already the longest by far, I will omit the “controversies” and “rebuttals” about the Lawton World Record. It would take another 75 pages or so. Should you want to get into that, you’ll have to get Volume I of my 2007, “Compendium of Muskie Angling History” from Amazon or eBay OR read about all world record controversies free here:

http://www.larryramsell.com/chapter-8—world-record-controversies.html

Or Lawton specifically here:

Arthur Lawton – 1957 – LARRY RAMSELL.COM

I am sure that there are many other Hotspots that I am not aware of even though I have fished muskies in 23 states and 2 provinces of Canada over the past 65 years. Any reader who knows of one or more Legendary or famous Hotspots, please let me know with a write-up of same and supporting photos if available and I will include them in a follow-up article(s).

Send it to me at: larryramsell@hotmail.com Thank you!

NOTE: Although the above has appeared in every Part so far, I have yet to receive any unsolicited input. Therefore, we are getting “very close” to the end of this series.