A group of high school students at STEM School Highlands Ranch in Denver has invented a dashcam-style device that uses artificial intelligence to detect wildlife on roads and warn approaching drivers. The device uses an infrared camera to scan for animals in the road and a special AI model to identify them. It’s now in its final prototype phase, and the team of young engineers hopes the invention can be used by drivers everywhere to cut down on the amount of wildlife-vehicle collisions that occur every year.

Singh and her teammates Dhriti Sinha, RJ Ballheim, and Bri Scollville decided wildlife collisions are a problem worth addressing. Around 5,000 collisions with wildlife occur every year on roads in their state, costing some $80 million annually, the Colorado Department of Transportation reports. Looking at the country as a whole, the annual number of wildlife-collisions climbs to more than one million, with roughly 200 human fatalities in a typical year, according to a 2008 study. It’s why deer are the deadliest animal in America.

Photo by Utah DWR

At first, the group wanted to create a noise apparatus that would scare deer and other wildlife away. But after discussions with various experts, including CDOT and Colorado Parks and Wildlife, it became clear that deterrence wouldn’t be an effective way to avoid wildlife collisions. (Ever honk at a deer only for it to stand there and stare at you?)

Read Next: The Key to Solving Big-Game Migration Conflicts? Roadkill

“Before finalizing our design, we looked at current solutions,” Singh says. “It’s important when creating new technology to look at what’s already there, and see how you can make it better. CDOT was spending millions on these signs. They’re expensive, they’re stationary, and people sometimes just ignore them. So a personal device that directly alerts the driver would be a lot better than a stationary device that people would ignore.”

Every expert the group spoke with liked to remind them of the challenges and roadblocks to such an invention, Chacon says. For the device to function reliably in Colorado’s varied weather patterns, it couldn’t be triggered by rain, snow, sleet, or debris kicked up by wind. It also needed to work in the dark, which is when most wildlife-vehicle collisions occur. Infrared, or thermal imaging, which is used in many trail cameras and an increasing number of optics (it’s also cause for some debate among hunters), seemed like the best answer to all these challenges.

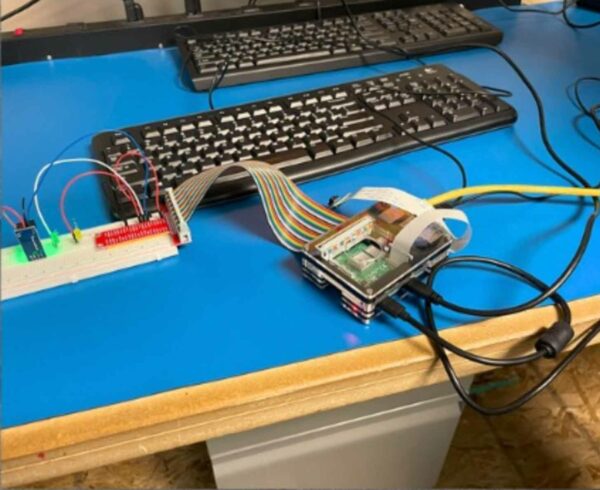

Photo courtesy STEM School Highlands Ranch

“Infrared is a wavelength emitted by many animals,” Scoville says. “It’s an efficient way to detect animals and other lifeforms, especially in lowlight and dark situations. If you’re driving at night, you’re not going to be able to see animals you might hit. We want the device to detect wildlife [well] before human vision would be able to detect it, because otherwise, the device isn’t doing much.”

The students’ latest prototype won the state level of the Samsung competition. Their prize package included some $12,000 in education tech, including laptops, a Smart Board, and a phone with a high-quality camera for their school to use. They distributed some of their prizes to other departments within the school and donated a cash gift card to a local elementary school to help fund a school garden. Although they failed to win at the national level of the competition, this doesn’t faze the group much.

Photo courtesy STEM School Highlands Ranch

“We didn’t exactly lose,” Sinha tells Outdoor Life. “You lose when you give up on the project. But we didn’t give up. We’re still working on it and refining our idea, so we haven’t lost.”

A lower-quality version of the device has already been tested on the school’s security dog while mounted on a remote control car. But the group has taken the device way beyond its initial design phase, Chacon says.

The group is currently preparing the final prototype and thinking about how to test it. They’re also looking for more infrared trail camera footage of deer to continue training the AI model on. The more infrared deer images the group can feed it, the more likely the model is to recognize a red blob with four legs and a head as a deer on the road. They hope to eventually train the model to recognize other wildlife species.

Chacon thinks the responsibility of testing the device on a real vehicle near real wildlife might fall on him, seeing as how none of the girls have their drivers’ licenses yet. But he doesn’t mind.

“Seeing them use some of the skills they’ve learned in engineering and computer science to build something no one has ever thought of before, it’s like the height of my work,” Chacon says. “This is the top prize. I feel like I won the championship belt of teaching.”